From the repeal of Prohibition to the response to the COVID-19 pandemic—charting AWC's advocacy for cities and the issues that have mattered most over nine decades

By AWC staff

Washington cities: The early years

The first two decades of the 20th century were a time of rapid expansion for cities in Washington. The state was relatively new, with 175 incorporated cities and towns. In 1910, Seattle Mayor Hiram Gill called city officials to Seattle to discuss the authority of cities to govern themselves (home rule), as he was deeply concerned about cities losing chartered functions to the Legislature and State Railway Commission. It was at this conference that the League of Washington Municipalities (LWM) was born—the first of several unsuccessful predecessors to the Association of Washington Cities (AWC), and the first practical demonstration of city officials gathering to seek municipal solutions.

In 1912, the University of Washington established the Bureau of Municipal Research and entered into a policy of cooperation with LWM. This cooperative continued until 1916, when the league disbanded due to lack of participation. Several other attempts to establish a statewide municipal league were made, but the main obstacles to success were a shortage of financial support and a lack of participation by larger cities. It was not until the era of the Great Depression that a permanent group was formed.

1930s

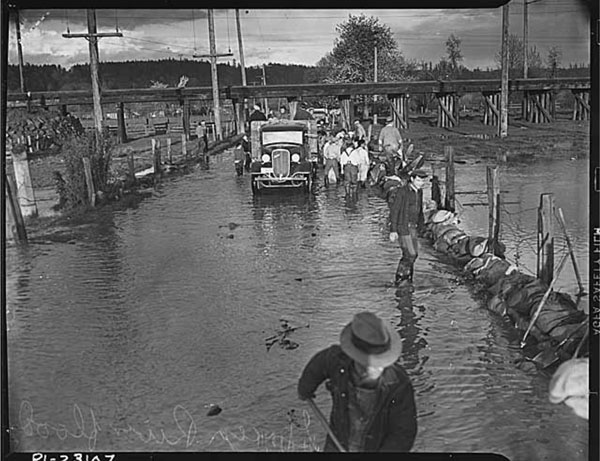

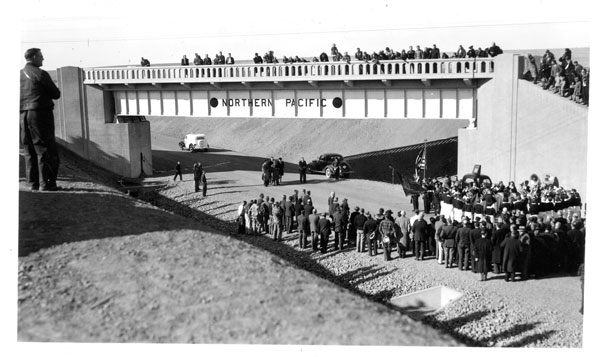

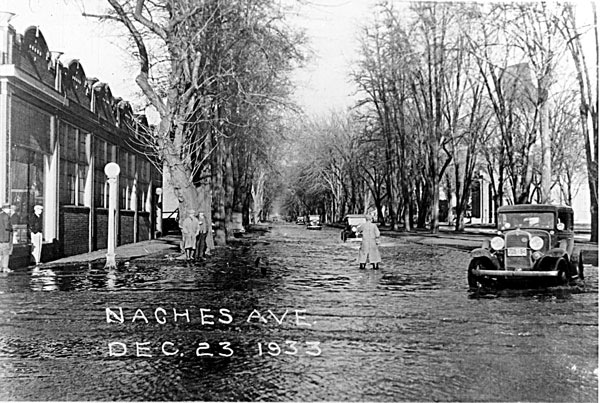

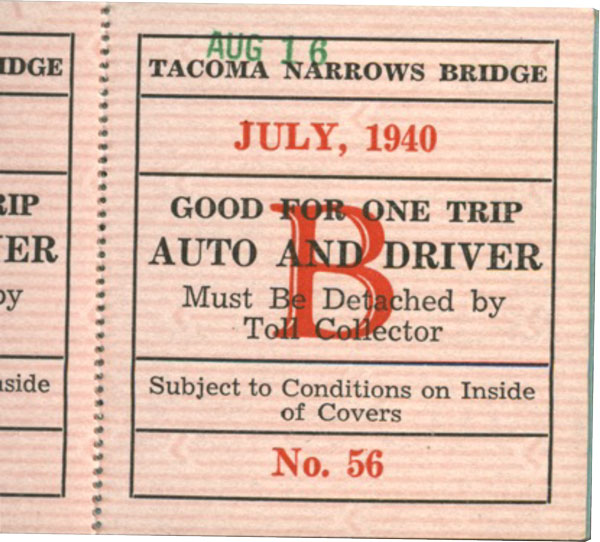

AWC was founded in 1933 after Prohibition was repealed and the issue of liquor control shifted to state and local politics. On October 26, city officials gathered in Yakima to present a united front on liquor control legislation. There, city officials voted to establish AWC to ask the state to share its new liquor tax revenues. AWC drafted the bill that eventually became the Washington State Liquor Act in 1934.

From there, AWC saw rapid expansion. In May 1934, AWC members gathered again at the Olympic Hotel in Seattle for the first annual convention to accomplish organizational business objectives. Since AWC was launched during the Depression, members were acutely aware of unemployment problems, and urged immediate adoption of a new federal work relief program. They also drafted a measure to give cities 25 percent of state highway funds, adopted AWC’s constitution, and reelected its Board Executive Committee.

In 1935, cities secured a share of the gasoline tax for local streets and highways. Governor Clarence D. Martin also signed the Revenue Act of 1935, the most comprehensive tax overhaul in state history. It has remained the foundation of the state’s basic tax system ever since, with regular, if relatively minor, changes.

In 1936, AWC intervened in court for its members to contest the power of the State Public Service Commission to regulate municipal water rates outside of city limits. In 1937, cities were given the right to establish recreation facilities and given control over the planning and subdivision of land. In 1938, AWC hired its first full-time lobbyist to represent 156 cities.

“Hardly a single session now passes without the adoption of a number of measures mandatory in cities,” AWC’s first CEO, Chester Biesen, noted at the time. “It [the state] mandates cities spend money they do not have and most frequently does not provide the means.”

City officials were enthusiastic, interested in AWC’s welfare, and were making valued friendships. Through hearing how other city officials had faced problems common to many, a comradery was built, which remains a cornerstone of AWC to this day.

Through hearing how other city officials had faced problems common to many, a comradery was built, which remains a cornerstone of AWC to this day.

1940s

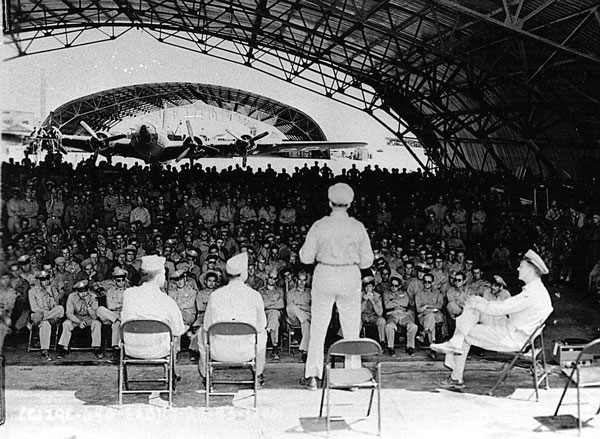

AWC’s chief concerns until 1946 related to helping cities prepare for civil defense and cooperating with the war effort, including several of AWC’s employees being reassigned elsewhere for war-related duties.

The nation plunged into a world war, and cities faced population increases, shortages of materials and labor, and the challenge of moving tremendous amounts of goods from Washington ports. As Congress began a defense buildup, Washington became a focus for war industries. Contracts and money flowed into the Puget Sound region for ships, planes, and tanks, bringing not only full employment, but a massive influx of war workers and their families.

One result of pent-up demand for new housing was the increased suburbanization of Puget Sound cities. As the armed services and war-related manufacturing drew labor, civilian Washington faced a shortage of workers. An inflow of labor from across the country began to diversify the population.

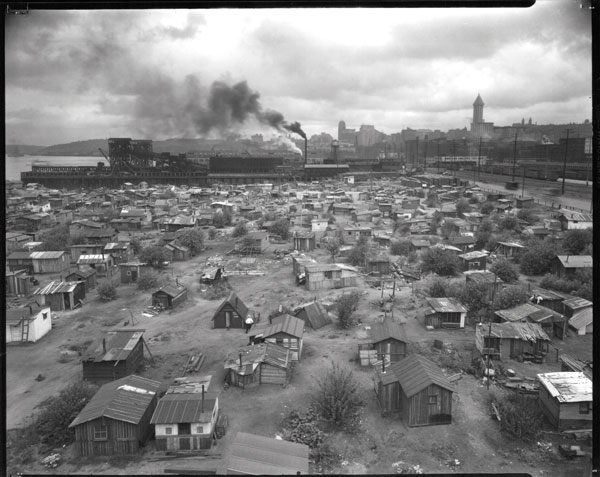

Public housing agencies were part of a national program during the Great Depression to eliminate slums, provide low-income housing, and alleviate unemployment. During World War II, the Tacoma Housing Authority built and managed housing for war workers and military families. In 1943, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began the massive and top-secret Hanford Engineer Works.

AWC’s chief concerns until 1946 related to helping cities prepare for civil defense and cooperating with the war effort, including several of AWC’s employees being reassigned elsewhere for war-related duties. Even so, AWC continued to expand and offer new services. During the later part of the decade, AWC was responsible for the passage of legislation establishing a retirement system for all city employees and sponsorship of the “road bill” which required the State Highway Department to maintain all state highways within corporate limits.

In the mid-1940s, AWC also encouraged groups of cities to meet regionally. Two organizations that were particularly active were the Association of Valley Cities (Kent Valley) and the Association of Snohomish County Cities. Valley Cities was a forerunner to today’s Sound Cities Association. Both regional associations still meet regularly today. By 1949, AWC had 231 member cities and towns.

1950s

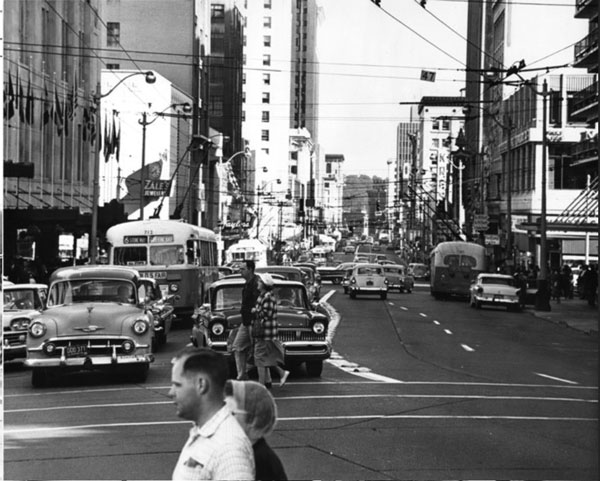

In 1950, the U.S. Census Bureau counted a huge increase in Washington’s population—a World War II baby boom.

In May 1950, President Harry S. Truman appeared before several thousand spectators at Gonzaga University in Spokane and gave a policy speech centering on racial equality. In his address, which became known as “the Gonzaga Speech,” Truman told the crowd, “We believe that no person—and no group of people—has an inherent right to rule over any other person or any other group.” Between 1950 and 1953, the U.S. was drawn into the first Korean War, and during that same time, experienced a polio epidemic. Millions of dollars were invested in developing and marketing a vaccine. Cities across Washington worked with school districts and local hospitals to organize massive vaccination programs.

During this decade, AWC underwent a major redefinition and reorganization. Its governing board was expanded to ensure equal representation of all cities on AWC’s Board of Directors. Grassroots participation in AWC continued to grow as the association suggested that all cities form legislative committees to develop a strong legislative program and identify vigorous local leadership to realize the organization’s objectives.

A series of schools were added for newly elected mayors and councilmembers, covering topics like job responsibilities and the problems of managing city utilities, land use, and finance. These schools were the forerunners to today’s biennial Elected Officials Essentials, held each December in odd-numbered (municipal elections) years.

In 1959, The state Legislature approved a new Planning Enabling Act, giving additional authority for counties to regulate land development and providing an option for counties to establish a planning department and a planning commission. It also called for the creation of a board of adjustment to consider applications for zoning permits and established specific requirements for comprehensive plans that contained a land use element and major transportation routes.

By 1959, AWC had 253 member cities and towns, representing 96 percent of Washington’s cities.

1960s

During the 1960S, cities and towns encountered more complex problems than ever. In response, AWC’s working committees became more specialized, covering sales tax, street design, public employees’ retirement, streets and highways, planning, and growth.

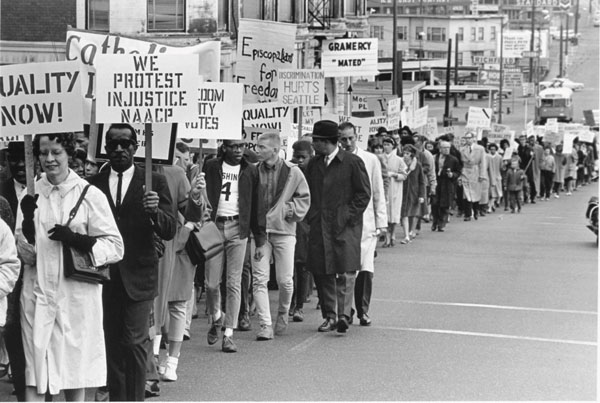

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on August 7, 1964, authorized the active involvement of the U.S. in the Vietnam War. Eventually, more than 8 million U.S. military personnel would serve, and fighting would spread from Vietnam to Laos and Cambodia. Washington state lists the 1,122 names of those who died in the Vietnam War—from the more than 58,000 Americans who died over the war’s 17-year period. Washington’s cities did not see an economic boom as they had in prior wars, with troops traveling overseas in jetliners instead of aboard troop ships. Seattle saw many war protests, including rallies, marches, and in extreme cases, bombings.

On February 26, 1963, Washington Governor Albert Rosellini convened the Washington State Commission on the Status of Women, using government data to assemble information on Washington state women workers. The commission made several recommendations, particularly focusing on the idea that the government itself and its agencies should end practices such as specifying “male only” and “female only” positions.

The federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 took major steps toward changing American society by prohibiting racial discrimination in public places such as restaurants, hotels, theaters, and schools. The act also required businesses and federally funded programs to abide by equal employment standards. The legislation attempted to rectify discriminatory voting practices, but results were weak in this area.

In 1967, the farm workers movement made its way to the Northwest. Founded in Washington in 1967 by two students from Yakima Valley College, the United Farm Workers Cooperative was the first Chicano activist organization in the state of Washington. The large concentration of Mexican Americans in eastern Washington made rural issues central to the activist movement that would soon emerge.

Cities and towns still struggled with urban growth and overstrained budgets. In 1967, the first general fund appropriation of $22 million was made to help hard-pressed municipal budgets. A $200 million highway bond program for urban arterial streets and passage of the Optional Municipal Code represented important legislative gains. The Municipal Research and Services Center (MRSC) was established in 1969 as an independent, nonprofit foundation funded by a portion of cities’ share of the motor vehicle excise tax. Working with AWC, MRSC provided research and service programs for Washington’s cities and towns.

At the end of the decade, AWC developed a group health insurance plan (the AWC Employee Benefit Trust), enabling member cities to take advantage of low-cost mass-buying power to purchase medical protection for city employees and their families. By 1969, 261 of Washington’s 266 municipalities had joined AWC, representing 99.9 percent of the state’s total city population.

1970s

In 1970, President Richard Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) sponsored by Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson. Often referred to as an environmental Magna Carta, the act required that federal agencies prepare environmental impact statements before taking major action, and it transformed government decision-making, becoming a powerful tool for environmentalists. Washington, like many other states, adopted the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA)—its most fundamental environmental protection law.

In 1972, Congress adopted the Clean Water Act to clean up the nation’s polluted rivers and streams. Municipalities were required to treat all wastewater before discharging it into waterways, prompting a boom in municipal wastewater treatment plants. Grants were distributed to help cities plan and implement projects. Provisions for protecting wetlands and managing stormwater drainage were added in later amendments.

To help correct some of the disparities between federal, state, and local revenue collections, Congress passed the State and Local Fiscal Assistance Act of 1972. This federal revenue sharing provided block grants to states and municipalities with fewer strings attached, so communities could address their most important priorities. Many cities used the revenue-sharing money to build capital projects. Others used the grants for recreation, transportation, and public safety.

In 1974, all of Washington’s cities and towns chose to join AWC for the first time in the association’s history. It has remained that way ever since.

Money continued to be a pressing need for cities. In 1970, after 15 years of effort to broaden the cities’ tax base, AWC successfully lobbied for a bill authorizing cities, towns, and counties to levy a local one-half cent sales tax.

In 1972, the Washington Local Government Personnel Institute was created to provide training and technical assistance in the personnel and labor relations arena. That same year, Washington state voters approved I-276, a predecessor to the state’s Public Records Act (PRA).

In 1973, oil imports to much of the Western world were drastically reduced by a coalition of Arab countries known as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). The embargo prompted the U.S. government to impose national speed limits, fix gas prices, and impose rations. The gas shortages affected the operations of local police, fire, and utility departments, and local government leaders had to develop ways to deal with the shortage. The crisis ultimately subsided after the embargo was lifted.

In 1974, all of Washington’s cities and towns chose to join AWC for the first time in the association’s history. It has remained that way ever since.

In 1978, AWC moved its staff to Olympia on a full-time, year-round basis.

1980s

Mount St. Helens erupted on May 18, 1980, killing 57 people. Destruction was widespread but especially severe in Clark County, as boiling gas and mud scoured 200 square miles of forest and destroyed 4 billion board feet of salable timber. The Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife estimated that nearly 7,000 big game animals on and near Mount St. Helens perished, including all birds and most small mammals. Downwind of the volcano, many agricultural crops were destroyed by ash. Interstate 90 from Seattle to Spokane was closed for a week. Airports in eastern Washington shut down, and sewage-disposal systems were plagued by ash clogs. State and federal agencies estimated that workers and volunteers cleared about 900,000 tons of ash from highways and roads. In a congressional study, the International Trade Commission determined timber, agricultural, and civil works losses reached $1.1 billion, which would be about $4 billion in 2023 dollars.

The 1981 legislative session was the first 105-day regular session. AWC moved into its current home in 1985, a former residence constructed in 1885 and renovated to retain many of its historical features.

The move to Olympia and city officials’ grassroots efforts paid off. The early ’80s saw the enactment of several major legislative goals, including a second one-half cent sales tax at the local level. But as crumbling infrastructures began to make headlines across the nation, the critical need for new streets and roads, bridges, water and sewer systems, and park facilities rose to the top of city priority lists.

In 1986, the U.S. Forest Service acted to protect the northern spotted owl from decline and extinction by limiting timber sales in mature portions of national forests, where the animals lived. The timber industry said that the measure went too far and would cost thousands of jobs, and environmentalists argued that not enough was being done to protect the owl and other species. A long series of governmental actions and court decisions resulted in a reduction of more than 75 percent of the timber harvested annually from public lands. The reduced number of logs had an economic impact on dozens of communities in the Northwest.

To deal with the problems of rising health care costs, AWC’s Employee Benefit Trust began a wellness program for cities to provide on-site health promotion programs for employees.

The state’s tort liability system underwent significant changes in the 1980s, and AWC began a comprehensive study to determine how cities could best deal with rising insurance costs. In response, AWC created its Risk Management Service Agency (RMSA), offering comprehensive property and liability coverage to members.

AWC’s Employee Benefit Trust began a wellness program for cities to provide on-site health promotion programs for employees.

1990s

Washington’s Legislature enacted the Growth Management Act (GMA) in 1990, on the last day of a special legislative session, transforming land use regulation in Washington.

The law was part of a growth management “revolution” triggered by voter frustration over the effects of rapidly increasing development.

It required the state’s largest and fastest-growing counties and cities to conduct comprehensive land use and transportation planning, concentrate new growth in compact “urban growth areas,” and protect natural resources and environmentally critical areas.

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 represented the first major rewrite since 1934. Intended to develop competition in the telecommunications marketplace, the act created opportunities for both telecommunications providers and local governments. The act also preserved the rights of local governments to manage their public rights of way and receive fair and reasonable compensation from providers.

In 1999, a 16-inch fuel line owned by the Olympic Pipe Line Company ruptured in Bellingham, spilling 277,200 gallons of gasoline into Hanna and Whatcom creeks. The volatile fuel exploded, killing three youths. In response to the tragedy, legislation was passed giving the state responsibility for regulating intrastate pipelines and improving pipeline safety, as well as allowing the Washington State Utilities and Transportation Commission to inspect 2,500 miles of intrastate pipelines and to oversee the state’s pipeline safety program.

By the end of the decade, the AWC Board of Directors had appointed an Urban Agenda Committee to review emerging issues. AWC launched two new programs: the Certificate of Municipal Leadership (CML) program and the Drug & Alcohol Consortium.

The AWC Employee Benefit Trust tackled continued rising health care costs by enhancing worksite health promotion programs for employees, creating the WellCity Program.

2000s

The technology boom of the 1990s helped local governments expand their services and capabilities, including allowing payments, recreation class registrations, and job applications to be made online.

GIS technology became a major tool for city planners and economic development staff. Residents could watch council meetings from their own living rooms with local cable channel access.

In 2000, the repeal of the motor vehicle excise tax resulted in many jurisdictions facing great difficulty in funding basic services. AWC successfully lobbied for backfill funding for the most adversely impacted communities. AWC also provided extensive technical assistance to help cities deal with the impacts of the repeal via I-695, the first of several $30 license tab fee initiatives.

In February of 2001, a magnitude 6.8 earthquake hit the state. The Nisqually earthquake shook the ground up and down the I-5 corridor and caused cracks in the dome of the Capitol building. Also in 2001, I-747 limited property tax increases to 1 percent, further limiting city access to funding.

Washington’s cities and towns participated in a worldwide moment of silence following the terrorist attacks on Washington, DC and New York City, which killed more than 3,000 people on September 11, 2001. Public officials joined with other local leaders in expressing their communities’ grief and calling for religious and social tolerance.

In 2003, AWC welcomed the newly incorporated City of Spokane Valley as its 281st member.

In 2005, the Legislature approved a 16-year, $8.5 billion transportation revenue package, which at the time was the largest infrastructure investment in state history. The program was funded by a 9.5-cent increase in the state gasoline tax. Voters that year decisively rejected an attempt to repeal the increase, keeping transportation spending in place.

Also in 2005, Senate Bill 6050 created ongoing funding for city financial assistance and Senate Bill 5177 created the Transportation Benefit District funding authority.

The state Supreme Court surprised many when it eliminated the most often-used method of annexation—the property owner petition method. AWC formed a coalition of business, environmental, and other stakeholders to craft and pass replacement legislation and petitioned the court to reverse its ruling—an unprecedented action.

To deal with rising Labor & Industries premiums, AWC formed the Workers’ Compensation Retrospective Rating program. AWC began leveraging data storytelling via a new series of State of the Cities reports to provide cities and the Legislature with data on the cities’ fiscal health, economic development efforts, and infrastructure conditions.

In 2008, the U.S. real estate bubble crashed due to the nationwide subprime mortgage crisis. The Great Recession followed, cascading into a worldwide financial crisis that would take years to recover from and impacted every sector of the economy.

In 2009, this magazine, Cityvision, sprung to life, using storytelling to highlight the most relevant city issues of the time.

AWC began leveraging data storytelling via State of the Cities reports to provide cities and the Legislature with data on cities’ fiscal health, economic development, and infrastructure.

2010s

The Great Recession hit cities hard, causing a decade of challenges in terms of both state and city budgets. Many city revenues were cut to the bone. AWC increased advocacy training to help cities get more involved with the Legislature. The “Strong Cities, Great State” campaign was born, with the goal of increasing cities’ involvement in the legislative process and building stronger relationships with legislators.

After several years of AWC advocacy on long-sought measures addressing the costs and challenges of 1970s-era statutes, modest updates to the Public Records Act (PRA) were made in 2011 and 2017.

In 2012, the state Supreme Court upheld the McCleary decision, requiring the state to meet the constitutional mandate to fully fund K-12 education. Hundreds of millions of dollars more in education were needed, and the ramifications hit the Public Works Assistance Account hardest. Eleven years later, cities are celebrating the return of those funds.

In a callback to AWC’s founding event, cities that year saw the privatization of liquor sales, again impacting state-shared revenues to cities. The legalization of cannabis impacted revenue sharing and local decision-making as well, as cities advocated for the ability to site cannabis facilities at the local level.

Statewide transportation, behavioral health, and affordable housing all became more important issues for cities. A divided Legislature meant a series of special sessions, highlighting the ongoing importance of united city voices. Cities lobbied for the passage of the 2015 Connecting Washington transportation package, which included $16 billion in investments to wide-ranging projects statewide, breaking the previous record from 2005.

AWC entered a lawsuit to challenge the constitutionality of the 2019 $30 car tab initiative, and successfully overturned it.

The “Strong Cities, Great State” campaign was born, with the goal of increasing cities’ involvement in the legislative process and building stronger relationships with legislators.

The “Strong Cities, Great State” campaign was born, with the goal of increasing cities’ involvement in the legislative process and building stronger relationships with legislators.

2023

Three years into the 2020s, the country has already experienced a global pandemic, community demonstrations in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, the Russia-Ukraine war, the increasingly violent impacts of climate change, and the rapid growth of artificial intelligence.

Through it all, cities have adapted, shifting the way they deliver services to establish a “new normal” for residents across the state.

Historic participation in government, together with massive federal investments via the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) as well as innovation at every level, have provided some relief and planted seeds for the future of our communities. From infrastructure and behavioral health investments, to striving for communities of belonging and leveraging partnerships and collaborations, cities continue to rise to new challenges through a combination of dedication and commitment to community.

AWC has expanded its work around diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB) by developing resources, establishing AWC’s DEIB Cabinet, and adding new training opportunities under the Certificate of Municipal Leadership (CML) program. In 2022, AWC advocated for another essential transportation package: the 16-year and nearly $17 billion Move Ahead Washington funding bill, another record- breaking investment.

We all gain strength and influence by working together with policymakers, pooling resources, and learning from one another.

As AWC proudly celebrates its 90th anniversary, the association is immensely proud of its enduring legacy of bringing cities and towns together to strengthen the foundation of Washington. We all gain strength and influence by working together with policymakers, pooling resources, and learning from one another.