By: Devon O’Neil

Renton’s longstanding culture of inclusion takes its cues directly from the top.

While the modern diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB) movement may be rooted in the anti-discrimination and civil rights movements of the 60s, the murder of George Floyd in 2020 compelled municipalities across the country, businesses, and organizations of all sizes to reevaluate how they were operating, whether their policies and protocols were inclusive, and whether their hiring practices and treatment of staff and constituents promoted equity. Many hired consultants and began to lay a foundation based on the principles of DEIB upon which they could build future policies that would stand up to scrutiny—both internal and external—and which would allow leaders and residents to be proud of where they live and work. The City of Renton, however, already had a DEIB program in place.

Washington’s eighth largest city (population: 107,500) began doing this work almost a decade earlier, just as Renton’s demographic makeup started to shift away from a white majority. And then, just as it does today, that mandate came from the top—and was pursued collaboratively. For years the Renton Business Plan has driven policy and funding through simple direction—the entire document fits on one side of a piece of paper. It was created not just by elected officials but also by department heads. As far back as 2012, following a conversation at the annual City Council retreat, Renton’s Council amended the city’s business plan, adding inclusion as one of its goals.

Renton, just south of Seattle, is home to Boeing, IKEA, and the Seattle Seahawks practice facility. WalletHub ranked Renton as one of the 15 most diverse cities in the US:

Statewide population: | Renton population: |

|---|

- 64% White

- 14% Hispanic or Latino

- 9% Asian

- 4% Black

| - 37% White

- 20% Hispanic or Latino

- 26% Asian

- 7% Black

|

The Council’s commitment to inclusion was proactive in its intent, and in 2014, Renton won a Cultural Diversity Award given by the National League of Cities to recognize “municipal programs that encourage citizen involvement and show an appreciation of cultural diversity through a collaborative process with city officials, community leaders, and residents.” Still, to those who looked more closely at the city’s progress, more work remained to be done.

A Renton cultural event: A traditional lion dance at Renton’s Lunar New Year celebration at city hall.

Credit: City of Renton

The city hosted cultural events and recognized ethnic holidays, but had no official policies or programs specifically addressing systemic practices and policies or other barriers to inclusion. Former Mayor Denis Law hired an inclusion and equity consultant named Benita Horn (who now works in that capacity for AWC). Slowly, DEIB gained tangible traction in Renton. In 2015, Law formed the Mayor’s Inclusion Task Force—a group designed as a communications liaison between City Hall and the community—and the following year created the Renton Equity Lens, a tool used to analyze city hiring practices.

Members of the Mayor’s Inclusion Task Force.

Credit: City of Renton

These initiatives put Renton ahead of almost every other Washington municipality on DEIB. Then, in 2019, residents elected Armondo Pavone as mayor. A restaurateur who opened his first Italian eatery in Renton in 1985, at age 20, Pavone, now 60, bolstered his already rich community ties by riding around on an electric scooter to ring doorbells during his campaign. He’s brought uncommon approachability to the job, engaging residents everywhere from City Hall to a local wine bar, where an employee often asks him to show up and talk to frustrated residents about issues they don’t always understand.

Renton Mayor Armondo Pavone.

Credit: City of Renton

Pavone, who served on the Renton City Council from 2013 until he became mayor, had heard grumblings that the Mayor’s Inclusion Task Force wasn’t effecting discernible change—something it was never meant to do. So, with the task force’s blessing in 2020 (still pre-George Floyd), he convened more than a dozen meetings with minority groups across the city and formed Renton’s Equity Commission in 2021. The commission reviews policies and programs and advises the Council on issues pertaining to equity; it’s the only group other than the Planning Commission that meets on the dais. Pavone also mandated the use of anonymous applications in the city’s recruitment process, and banned the use of identifiers (including a candidate’s name, address and past salary information). “The idea is [to address] those unintended consequences that come from biases that you don't even know you have—you eliminate them,” says Pavone (he/him).

“The idea is [to address] those unintended consequences that come from biases that you don't even know you have—you eliminate them.”

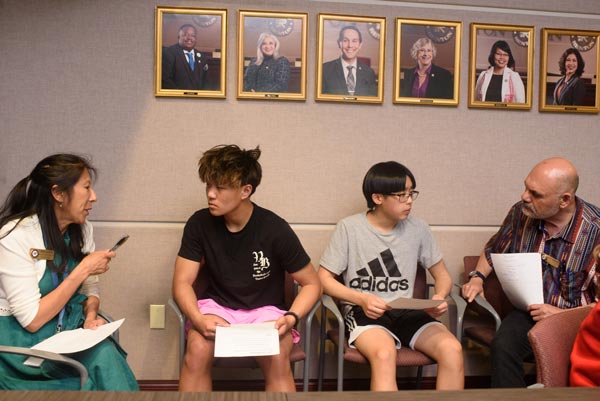

The Mayor’s Inclusion Task Force meets.

Credit: City of Renton

Still, Renton’s boldest move came in July, 2021. Even with a heightened focus on DEIB, its efforts on the different initiatives had long been siloed, just as they are at most municipalities. So Pavone and his colleagues created something new: the Department of Equity, Housing, and Human Services (EHHS). They pulled equity from the mayor’s office, housing from Community Development, and human services from Parks. The department is run by Maryjane Van Cleave, a longtime city employee who has served as director of Communications and Engagement and has overseen the Recreation and Neighborhoods Division. Aside from the novel concept, EHHS does something else that distinguishes it. It focuses on measurable data, not just to establish need and steer funding, but also to report back to the council on whether its allocations and decisions are succeeding. As Van Cleave likes to say, “You can’t improve what you can’t measure.”

“You can’t improve what you can’t measure.”

Maryjane Van Cleave at Renton City Hall.

Credit: Daniel Berman

The momentum hasn’t stopped there. Last year, Renton’s leaders added verbiage to its already strong business plan, making it more urgent than the one in place before Floyd’s death. Instead of simply directing leaders to “seek out opportunities for ongoing two-way dialogue with ALL communities,” as one of the points read, it now includes an initiative to “engage those historically marginalized, and ensure that we lift every voice, listen, and take action on what we learn.” As well, a new bullet point more precisely spells out the intent: “Achieve equitable outcomes by eliminating racial, economic, and social barriers in internal practices, city programs, services, and policies such as hiring and contracting.”

Mayor Pavone engages with members of the Mayor’s Inclusion Task Force.

Credit: City of Renton

The evolving goals come in response to a rapidly changing population. Sixty-three percent of Renton residents are BIPOC, up from 46 percent in 2010. Thirty-eight percent of residents speak a language other than English as their primary language. The number of immigrants from Asia, South America, Central America, and Eastern Europe residing in Renton continues to grow, with the immigrant population comprising 28 percent of the city’s total. Despite a median household income of $83,699, the median home value—$749,000—remains out of reach for many.

While Renton may not be as diverse as Kent (which placed sixth on WalletHub’s 2023 ranking of the most ethnically diverse cities in the United States; Renton was 15th), but its leadership does reflect the city’s demographics. The seven-member council includes two Black men, a queer woman, two Latina women, and a Vietnamese immigrant. Two who are serving their third terms, Ed Prince and Ruth Pérez, have particularly unique ties to the subject: Prince is the executive director of the Washington State Commission on African American Affairs, and Pérez, who is Mexican American, was the first Latina and first immigrant to ever serve on Renton’s City Council. “That just speaks to how we have embraced our constituents,” says City Council President Valerie O’Halloran (she/her), who has lived in Renton for 28 years. “So that we look like them.”

Members of the Mayor’s Inclusion Task Force engage.

Credit: City of Renton

To keep a finger on the community’s pulse, Renton also employs a Neighborhoods Coordinator and uses a custom app (a la Nextdoor) called In the Loop, specifically designed to connect staff and leadership with Renton’s diverse citizenry—including a two-way communication feature that lets residents submit feedback to the city. Every member of the police department, or roughly a third of the city’s 600 employees, is required to complete 12 hours of DEIB training—a significant and ongoing investment.

Renton, of course, is far from the only city in Washington leading by example on equity and inclusion. Bellevue has had a Diversity Advantage Plan in place since 2014, to “put the positive power of diversity to work in our community.” Last year Kirkland adopted a five-year DEIB Roadmap that will be reviewed and updated regularly. The City of Bainbridge Island formed a Race Equity Advisory Committee that meets monthly. And in February, Kent’s City Council adopted a Race and Equity Action Plan and is spending $462,000 to implement it this year.

If there’s one truth among all these cities, it’s that DEIB policies are only becoming more important as their populations become more diverse. In Renton, for example, 74 percent of the current non-white population is younger than 21—a clear metric to drive future planning.

“Inclusion isn't just about race anymore,” says Carmen Rivera (she/her), 32, the first openly queer person and youngest Latina to be elected to Renton’s City Council. “Yes, we're becoming a very diverse city, but we also need to look at veteran status, religious background, sexual and gender diversity, renter versus homeowner versus houseless status, immigration status, disabilities, even the opioid epidemic—that'll help us determine what we're going to fund.”

Rivera credits a vocal constituency for Renton’s reputation as a municipal DEIB trailblazer. “The community is loud, and the liaisons between the city and its residents work hard to push status quos,” she says. As people continue to move south to escape Seattle’s ever-increasing cost of living, those factors will only become more influential. “We're going to have an even more diverse city in 10 to 20 years. How are we setting them up for the future?” asks Rivera, who also sits on AWC’s DEIB Cabinet. “I talk with staff and get excited about how they are really in tune with the community's needs. And not just in a way that makes me feel good. It makes me feel hopeful.”

“We're going to have an even more diverse city in 10 to 20 years. How are we setting them up for the future?”