Cheney applies lessons learned from agrarian prudence, main street entrepreneurship, and the local university to revitalize its unique community spirit.

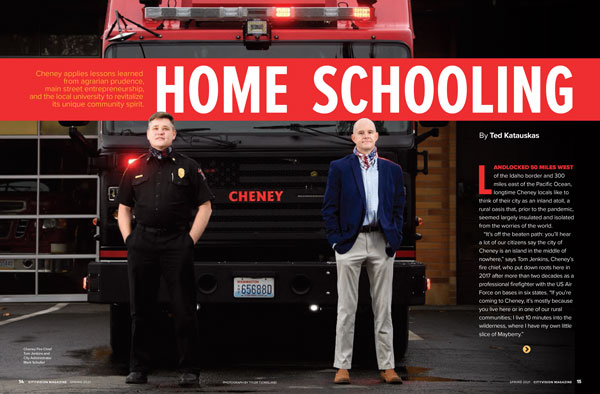

Cheney Fire Chief Tom Jenkins and City Administrator

Mark Schuller

Landlocked 50 miles west of the Idaho border and 300 miles east of the Pacific Ocean, longtime Cheney locals like to think of their city as an inland atoll, a rural oasis that, prior to the pandemic, seemed largely insulated and isolated from the worries

of the world.

“It’s off the beaten path: you’ll hear a lot of our citizens say the city of Cheney is an island in the middle of nowhere,” says Tom Jenkins, Cheney’s fire chief, who put down roots here in 2017 after more than two decades

as a professional firefighter with the US Air Force on bases in six states. “If you’re coming to Cheney, it’s mostly because you live here or in one of our rural communities; I live 10 minutes into the wilderness, where I have my

own little slice of Mayberry.”

Surrounded by the pastoral agricultural tableau of the Palouse just 20 minutes southwest of Spokane, Cheney’s resident population of 12,500 prides itself on being a close-knit community where self-sufficiency and a can-do work ethic are worn like

a badge of honor, yet everyone knows and looks after one another—and helps when needed. Two years after retiring as the City of Costa Mesa’s police chief in 2006, John Hensley was so enamored with life in Cheney that he decided to reprise

the role in his adopted hometown.

“I moved up here because of the four seasons and the beauty of the landscape,” says Hensley. “After 12 years, I take it for granted how friendly folks are compared to Southern California. I spend a lot of time driving around in a marked

police car, and I still am surprised at the waves I get, and how everyone flags you through a four-way stop. It’s just a small-town feel that you see on TV sometimes when you watch a Hallmark Classic.”

Even kids born and raised in Cheney tend to move back once they’ve experienced life in the wider world. After graduating from Cheney High, then Portland State University, then the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Piedmont, Italy (founded by

Carlo Petrini, who pioneered the global slow food movement), Douglas LaBar returned to his hometown in 2012 to open a locally sourced gourmet café, The Mason Jar, in the heart of Cheney’s four-block historic commercial district.

Cheney native Douglas LaBar returned

after an educational stint in Italy to open a gourmet café downtown.

“I made it my master’s thesis project to come back home and open a bistro using small farms to bring attention to localization in the community,” says LaBar. “Downtown Cheney was definitely dead then. To try just getting people

into the old part of downtown, never mind participate in my take on things, was a challenge, but we’ve adapted and changed and have become a staple of the community.”

In addition to hosting cooking classes for the city’s Parks & Recreation department, as well as festivals and community events (like a scones and tea reception for the local historical society) and a forum for guest lecturers from the university,

business was so good a year ago that LaBar opened The Jar, a satellite drive-through near Eastern Washington University catering to students and faculty commuting to and from campus.

“Cheney is kind of a split-personality town,” he adds. “It’s half rural, small town surrounded by wheatland farms, so you get that essence. But then the college is here, the university, so there’s also this split dynamic,

with lots of education and a liberal side, that brings this bustle and energy to the community.”

Predating Cheney’s incorporation, Eastern Washington University is almost a separate city unto itself, with an enrollment that rivals the city’s resident population and inspires a fierce allegiance to the Eagles, with as many local residents

as students packing the bleachers at Reese Court for basketball and attending Saturday afternoon tailgate parties at Roos Field, a football stadium with red turf.

“Cheney is a special place,” says City Administrator Mark Schuller. “There’s an energy in the community, and a lot of that is tied to Eastern. Every fall, when you have a new incoming class of students returning, there’s

an excitement in the air that really drives the community. After a long dry summer when businesses tend to suffer a little bit, they come back with a vengeance when the kids return. This past year has been problematic in that the kids didn’t

come back.”

Schuller moved to Cheney from his Ohio hometown in 2003 to work as a human resources administrator at EWU (his wife coaches the university’s women’s basketball team), then as human resources manager for the city in 2009, becoming city

administrator in 2014. By the end of 2019 the city had emerged from recession-era austere budgeting championed by Cheney’s mayor and council that developed a habit of socking away cash reserves, adopting a save-rather-than-spend approach

that mirrors the community’s ingrown agrarian savvy: learning to do without niceties even when flush with bumper-crop revenue in anticipation of lean times to come.

“We’ve referred to ourselves in the past as a Ford city, not a Mercedes city, meaning we don’t overspend on luxury that doesn’t contribute to our ability to serve,” explains Schuller. “Being proper stewards of our

resources is something we take a tremendous amount of pride in as a city It’s a bit of a cliché, but we do a lot with a little every day.”

Cheney’s austere budgeting is also a practicality born out of necessity, given constraints dictated by a cash-starved local economy.

“Over the past decade, one of our biggest challenges has been finding revenue to support our general fund,” notes Schuller. “We don’t have a huge retail base in Cheney; we have a lot of fast food and those kind of low-income

retail establishments. We don’t have car, RV, or farm implement dealerships, so we don’t get those big dollars in sales tax.”

“We’ve referred to ourselves in the past as a Ford city, not a Mercedes city, meaning we don’t overspend on luxury that doesn’t contribute to our ability to serve.”

– Mark Schuller, Cheney City Administrator

In contrast with the dynamic in Pullman, where according to one recent study Washington State University’s much larger student body injected nearly $50 million into that city’s economy during the 2018–19 academic year, student spending

isn’t the life- blood of Cheney’s economy. With 81 percent of EWU’s undergraduate population living off campus or commuting from elsewhere in the region, the university’s cash-poor student population exerts an important

but comparably minor influence on Cheney’s bottom line. Far more influential are EWU’s 3,000 full-time employees; the university is easily the city’s largest employer, followed by the school district, with 492 full-time employees

at 12 public schools, and the city, with 88 full-time employees. But even that spending is eclipsed by EWU’s operating budget, which depends largely on enrollment—which has been declining in recent years—as well as appropriations

from the state Legislature.

“I kind of run by the mantra, ‘As Eastern goes, we go as a city,’” says Schuller. “Typically, when Eastern is doing well, the economy is doing well, and we do well as a city because they are investing in infrastructure

and doing things like creating jobs. When times are tough for them, generally we’re going to be in those tough times, too.”

When the pandemic emerged last spring, shelter-at-home orders, coupled with a mass exodus of students as the university shifted to online classes, transformed Cheney’s normally bustling downtown into a ghost town. Yet while other cities dependent

upon retail-based sales tax revenue reeled from the impact of nonessential business closures, cash continued to flow into Cheney’s coffers, as construction at the university (in the final stages of a $68 million Integrated Science Center)

and the school district (a major expansion of the high school) continued unabated, with the city posting a 20 percent increase in revenue during the first quarter of 2020 and a 12 percent increase from the previous year during the second quarter.

By the end of summer, however, as construction activity slowed and the pandemic exacted its toll on the finances of the city’s largest employer (faced with a $24 million shortfall in tuition and state funding, EWU instituted a series of cost-cutting

measures that included layoffs, salary reductions, or furloughs for 400 employees), Cheney’s third-quarter revenues nosedived by more than 14 percent compared to July through September 2019, while fourth-quarter revenues were off by nearly

24 percent. Based on those ominous trends, Schuller and city leaders budgeted accordingly.

“Top priorities for funding were items that directly related to our ability to provide a high level of service to the community, city financial liabilities, and items related to employee safety,” Schuller explains. That included debt service

payments for a recent wastewater treatment plant upgrade and the recent acquisition of a fire engine, as well as the purchase of personal protective gear for firefighters and police officers. While the city decided to forgo augmenting police riot

gear—with its activist student population on hiatus, Cheney experienced none of the social unrest over policing practices that many other cities grappled with over the summer—it opted to fund additional de-escalation and inherent bias

training for its 17.5 sworn officers.

And while the city continued to fund street sweeping and maintenance of municipal parks and playgrounds, it took a year off from the scheduled replacement of police patrol cars and fleet vehicles used by Parks & Recreation and utility workers.

It also deferred the replacement of office furniture at city hall, as well as a citywide computer operating system upgrade. Those savings enabled Cheney to forgo employee layoffs and furloughs, while carrying a cash reserve of $446,550 into 2021.

“We worked diligently as a city to build our reserves back after a low point in 2012, as the city dealt with the fallout from the recession and a significant lack of tax revenue,” Schuller says. “We made the decision to maintain

our current level of reserves, as we have some concerns about the length of time it will take for sales and other tax revenue to return to the pre-COVID levels.”

The conservative, yet cautiously optimistic, economic planning modeled by the city resonates with businesses along First Street in the city’s historic commercial district. At The Mason Jar, LaBar now appears prescient in his decision to debut

an online ordering system in September 2019, along with asking the city to restripe the curbside parking outside the café as a designated 10-minute grab-and-go parking zone. Hoping to alleviate the lunch rush and streamline ordering, the

service was all but unused for six months—until the pandemic did what no amount of promotion could.

Cheney Faith Center Lead Pastor Mark

Posthuma helps run a community food bank that's been busy in the pandemic.

“We had all this ready, and lo and behold, [the pandemic] happens and we’re good to go,” says LaBar, who also serves as president of the Cheney Merchants Association. “We did have to shut down inside seating, but we were able

to switch from that day straight on to ordering online. Those sales just picked up like crazy, and we didn’t have to reinvent the wheel like some other people I know.”

LaBar was gratified that years of pitching a buy-local campaign resonated with the community: residents were spending their stimulus checks at The Mason Jar and other local eateries, and tipping generously. After receiving a federal grant, Spokane’s

Meals On Wheels began offering seniors vouchers to redeem at area restaurants, and LaBar noticed a similar uptick of orders from older diners and their caregivers. All told, the restaurateur, who employs as many as two dozen staff at both venues,

says business during the pandemic has been off by 30 percent, far better than he could have expected.

The city’s restaurants even benefit from their own local delivery service. Prior to the pandemic, after trying in vain to lure national apps like DoorDash and UberEats to Cheney, LaBar and two other Cheney restaurateurs connected with Treehugger,

a Spokane-based grassroots delivery service that allowed Cheney businesses to use its online app and digital platform. Local drivers for the city’s own Eagle Bites (named after EWU’s mascot) now earn more than they could with national

services, and they provide restaurants with a cheaper alternative to national delivery chains as well.

“That’s kind of our ethos, our push as a community,” says LaBar. “We’re trying to find people who already have talents here to do lots of different things. Rather than trying to go outside our community and bring it in,

we get people who are really invested already because they live here.”

As much as they would like to invest in their community, though, many Cheney residents can’t afford to eat out, or for that matter, buy groceries. More than a third of the local population had been earning less than the federal poverty level

before the onset of the pandemic, which only made matters worse. So since April 2020, volunteers at the Cheney Faith Center have been staffing a drive-through food bank that distributes 2,000 pounds of donated provisions each week, loading boxes

of milk, produce, and staples into the trunks of as many as 100 cars that queue outside Cheney Middle School every Wednesday afternoon. In addition to food, the Faith Center also has doled out $7,000 that parishioners have contributed to an emergency

fund for those who need help paying utility and electric bills.

“Those who were financially insecure before, this has hit them hard,” says Mark Posthuma, Cheney Faith Center’s lead pastor. “When you’ve lost your job and were making $3,000 a month, to go to $600, that hurts.”

Then there’s the spiritual toll.

“The social and emotional impact has been significant,” says Posthuma, who also has been fielding an uptick of calls from community members who have been experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression. “It’s kind of a catch-22:

the thing we need to do we can’t do, and that is start getting together…There was this great environment that the city created, this really cool atmosphere in Cheney. All that went away, and that is tough.”

One barometer of just how tough is the number of calls for help that have flooded the city’s 911 system since the onset of the pandemic. With more than 11,000 students AWOL throughout most of 2020, Cheney’s police chief expected the call

volume to decrease significantly; instead, year-to-date calls dropped by just 1.7 percent, from 29,103 in 2019 to 28,600 in 2020, driven by the city’s distraught resident population.

“Because people have been sheltering in place, there’s been a lot of anger and wondering about what the future may bring—people living on edge because they’ve been cut back on work hours, and they take it out on another,”

says Hensley. “In the past, domestic violence was maybe three or four, after minor thefts, assaults, alcohol-related calls. Now it’s our number one call.”

Mental illness–related calls also have been on the rise; Hensley says the number of voluntary commitments from Cheney to Spokane’s psychiatric hospital is the highest it’s been since he arrived over a decade ago. And then there are

calls like the one from a college student who just wanted to talk.

“Rather than trying to go outside our community and bring it in, we get people who are really invested already because they live here.”

– Douglas LaBar, local restaurateur

“She didn’t go home, and she was lonely,” he says, adding that the department’s chaplain masked up and sat with her while she initiated a Zoom call with her family to make plans to return home. “That broke my heart. The

isolation is starting to get to people, the cries for help.”

Similarly, emergency calls to the city’s fire department have remained constant despite the falloff in student population, decreasing by a mere 0.7 percent. The majority of those calls is medical related, with perhaps 20 percent concerning psychiatric

issues. While morale in his department remains high, Jenkins watches for signs of critical stress in the department’s 11 full-time and 18 volunteer firefighters, given the nature of those calls and their ties to the community.

“These guys were all born and raised in this community; they know every address like the back of their hand,” he says. “Seeing loved ones, friends and family, coworkers and kids you grew up with in school, their moms and dads suffering,

that adds another layer of stress...To say that this city is in crisis mode—no, I think we are in survival mode. And a large part of that is because our older demographic population has been through life, and they either lived through the

Great Depression or they remember their mom and dad talking about the Great Depression. That’s the generation that needs to say, ‘Young folks, it’s going to be OK. We’re going to get through this.’”

For that to happen, those young folks will need to return in the fall, as EWU is planning.

Eastern Washington University Interim President David May

“In a town like Cheney, the university is a lot more than just an economic driver,” says EWU’s interim president, David May. “We’re the entertainment on the weekends, with football games and basketball games, the theater,

art exhibitions, student clubs and organizations putting on events The vibrancy that a few thousand more young people bring to a community, to a college campus, is missing this year.”

But there have been positives.

“It’s hard to talk about bright spots in the midst of what we’re all going through right now, but I think we have proven we can do things that we used to be quite vocal about not being able to do,” he adds, referring to the

university’s pandemic pivot to remote learning. “We would say it’s not possible to deliver this lab course online, and yet now we’re doing it because the impossible is only impossible until you have to do it.”

In that spirit, the city, like many rural communities long constrained by and frustrated with substandard commercial internet service, plans to debut a pilot project in the spring: a city-run internet utility, offering residents broadband access for

just $60 a month.

“The pandemic accelerated people’s outreach to us to say, ‘We really need you guys to step up and work on this for us,’” says Schuller. “One of the silver linings is just the resiliency of this community. Cheney

has been a very resilient community for a long time. We’ve weathered a lot of storms, whether it was the recession in 2009 to 2012 or today’s pandemic.”

For one, and like most in Cheney, Schuller longs for the day when that maelstrom has passed, “when we can get back into Roos Field, that nice red AstroTurf field, and watch the Eagles play, and things are back to normal.”

And the home team wins.