In 2016, the Kirkland Police Department had a serious problem. “We began to see a number of retirements,” says Chief Cherie Harris. “And not just retirements: officers were moving to other professions, we lost some officers to the private sector, and some officers went to departments located elsewhere in the state.” The department was short 10 officers that year, which meant big changes in terms of its community presence.

“We had to pull everybody back from our specialty units,” explains City Manager Kurt Triplett. “We prioritized keeping our patrol slots filled, but to do that we had to pull people out of our traffic unit, which has impacts on congestion management and safety and collisions. We had to ask certain officers not to be a school resource officer, as an example, and come back on patrol.... It really did impact our good quality-enhanced services that we provide to be a full-service city.”

Kirkland’s not unique in its police staffing woes. In Lake Stevens, as just one example, Chief John Dyer echoes Triplett’s concerns. “One big challenge for smaller departments is that one or two vacancies constitutes a much larger percentage of the workforce than in larger departments,” he says. “This has a significant effect on operations, as well as on the health and well-being of the other squad members, with reduced time off and a greater workload.”

Nationally, it’s an issue, too. A Washington Post article from 2018 points to a stagnating interest in police work that’s currently affecting application rates at 66 percent of the country’s police departments, partly due to “a diminished perception of police in the years after the shooting and unrest in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014 and an increase in public and media scrutiny of police made possible by technology and social media.” According to the Post, over a quarter of new recruits at nearly 400 police departments across the country left their jobs voluntarily after less than a year, and the number of full-time sworn officers per 1,000 US residents has dropped from 2.42 in 1997 to 2.17 in 2016.

Exacerbating the situation, the average retirement age for police officers across the country is 55, with police in the state of Washington eligible for retirement (and pension) at 53—in other words, the baby boomer generation of police officers is simply retiring faster than new recruits can replace them. Shortages in department staffing affect retention rates, too, as officers have more flexibility to move laterally to other departments offering increasingly lucrative pay and benefits packages; Kirkland itself currently advertises a $16,000 hiring bonus for new lateral hires in an effort to woo staff from other departments.

Even though Kirkland officials were acutely aware that the city’s police department was hindered by this trend, a more aggressive hiring push met with yet another challenge. In Washington, state law requires new recruits to graduate from the state’s Basic Law Enforcement Academy before they can be deployed on city streets. At the academy, soon-to-be cops must complete 720 hours of coursework, covering everything from proper firearm handling to day-to-day patrol procedures to communicating effectively with diverse segments of the population—“It’s almost like going to college for five months,” says Harris. Yet the academy had nowhere near

enough slots in its program to accommodate the number of new hires being added at police departments across the state to fill staffing shortages. For cities like Kirkland, getting new recruits en-rolled at the state academy ended up being an even bigger hurdle than finding prospective new hires to replace their outgoing cops.

“The biggest issue was really the budget the academy gets from the state,” says Harris. “They get enough money to run only a certain number of classes every year.”

The biggest issue was really the budget the academy gets from the state. They get enough money to run only a certain number of classes every year. - Cherie Harris, Kirkland Police Chief

“You already have a challenge to get people to go into policing

because of the national narrative around conflicts between police and minority communities, and all of us [cities and towns] are

experiencing vacancies due to retirements, and then you’ve got to go aggressively recruit,” adds Triplett. “That’s where the academy limitations have been a real problem: because the competition for new people is so fierce, you have to hire new officers even before you know they have an academy slot.”

And pay them a starting patrol officer’s salary ($5,774 per month in Kirkland) to retain them in the meantime—even if they can’tbe deployed because they haven’t completed the state-mandated academy course. The bottleneck prompted Chief Harris to partner with Kirkland’s lobbyist in Olympia and the city’s state representative (and former Kirkland city councilmember), Shelley Kloba, to advocate for a bigger budget for the academy so that it could host more classes. That effort happened in coordination with a full-court press by AWC and municipalities around the state, who ultimately convinced state legislators to sign a letter to the governor advocating for a boost in the state budget to address staffing shortages in police departments statewide. And on a parallel front, Harris participated in the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs “Law and Justice Day,” a targeted lobbying effort at the capitol at which uniformed brass met with state legislators to explain how the academy class shortage was hurting policing at departments in cities and towns around the state.

“I actually became the police chief in 2016, so that was the first time I had really been involved in any type of lobbying,” says Harris. “The City of Kirkland is very organized, and support for more academy classes has been on their legislative agenda since I’ve been the chief.”

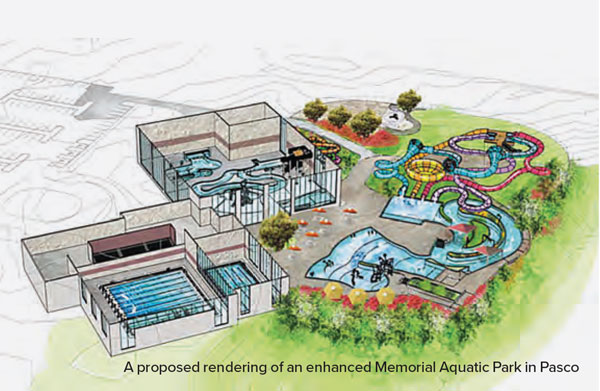

Meanwhile, on the east side of the state, for the past decade leaders at the City of Pasco have been mired in a different kind of blue (aqua) over their inability to fund regionally scaled all-weather additions that are desperately needed to augment Memorial Aquatic Park, a seasonal outdoor swim facility with a 50-meter lap pool that serves 74,000 residents and is only open May through August.

“This is a Tri-Cities issue: the Richland High School dive team has to go to Yakima to practice, and another high school’s swim team’s home pool is in Walla Walla,” says City Manager Dave Zabell. “So there’s a need competitively, but we’ve also heard from a lot of folks who really want this to be a signature facility that will draw people to the community as a destination.”

This is a Tri-Cities issue: the Richland High School dive team has to go to Yakima to practice, and another high school’s swim team’s home pool is in Walla Walla. - Dave Zabell, Pasco City Manager

Not that Pasco has a problem attracting newcomers. Blessed with a thriving oenotourism scene (with 200-plus wineries within a 50-mile radius) and a sublime climate (300 days of sunshine a year), the population of the Tri-Cities (Pasco, Kennewick, and Richland) swelled by 36,400 between 2010 and 2018, with Pasco alone accounting for nearly half of that growth. And the region expects to add another 112,000 residents over the next 20 years. As the area workforce has expanded, employers like the US Department of Energy, Gesa Credit Union, and Cascade Natural Gas have added hundreds of thousands of square feet of commercial space.

To meet the demands of all that growth, Pasco has been investing in expanded public services and capital improvements. The city’s $450 million 2019–20 biennial budget includes a new animal shelter, four new police officers, and a sewer line extension to serve the rapidly expanding commercial and residential area in the city’s west end. But budgeting for an indoor aquatic center, however sorely it may be needed, has remained a pipe dream in large part because of the rules governing the Tri-Cities Regional Public Facilities District (PFD).

The only multicity PFD in the state, the Tri-Cities Regional PFD formed when Richland, Kennewick, and Pasco banded together in 2010 to pool funding for shared public facilities projects. For just about as long, there’s also been regional interest in building an aquatic center in Pasco, with heavy support from city residents as well; the city had even picked a location for the new facility on Broadmoor Boulevard in west Pasco. But when the issue of raising funds for the new aquatic center (with an estimated price tag between $20 million and $30 million) went to the ballot, the effort failed.

“We had a vote on an aquatic center; however, the majority of the voters in all of the cities has to approve it because it would be a regional sales tax,” explains Zabell. “The measure passed by a pretty healthy margin in Pasco, but it failed in the other cities.”

So Pasco city leaders explained their dilemma to state legislators, which led to the introduction of House Bill 1499 this past spring. The bill’s language effectively allows members of multicity PFDs (that have populations between 160,000 and 1,000,000 people) to work autonomously from their regional shareholders to fund and maintain recreational centers (aside from ski areas)—meaning that when the bill was signed into law by Governor Inslee in May, Pasco voters were granted the right to vote separately from their regional neighbors in Richland and Kennewick on whether to raise the sales tax exclusively within Pasco to fund their long-yearned-for aquatic center. Keys to the bill’s passage were its careful wording, which doesn’t allow the new aquatic center to be dually used as a fitness center (and thereby threaten the viability of privately owned fitness centers in the area) and bipartisan support for the legislation from lawmakers in Olympia, thanks to a continued deluge of support from Pasco’s local representatives.

“The Tri-Cities PFD is well-intentioned, but in this case the PFD really wasn’t enabling individual cities to get done what they wanted done for their city. The way I looked at it was that I represent Pasco, and it was one of their priorities,” explains Pasco’s state representative, Bill Jenkin, who owns a winery in nearby Prosser and co-sponsored the bill that was ultimately signed into law. “A PFD can sometimes mean taxes, which is why it can be hard to get bipartisan support, but in this case I’m not creating the tax: the tax will be created when they take it out to the voters, if they decide that’s what they want.”

And that’s still an “if”—the soonest Pasco voters would be able to vote on the tax increase is 2020, and that’s if Pasco’s city council has approved a final price tag and design for the facility; at a meeting this fall, the city’s PFD board nixed prior design plans that incorporated a gymnasium and workout space.

“75 to 100 percent of the funding will be coming from within Pasco,” says Zabell. “And there actually is a mechanism now to make it happen—our voters have expressed a continuing support of the concept of bringing and building an aquatic facility to serve the community and the region....Now they can vote on whether they’ll tax themselves to do it.”

Jenkin—who also co-sponsored three other bills signed into law last legislative session—agrees that the issue ultimately comes down to local control, and that his peers on both sides of the aisle in the Legislature seemed to understand that, too. As to whether the vote will be approved by residents in Pasco whenever it ultimately reaches voters, he’s not as sure.

“I’m really interested to see what happens with it,” he says. “I want it to be good for Pasco, and I want it to also be good for businesses in Pasco.”

The same might be said for the potential in police staffing: thanks to lobbying efforts by Kirkland, AWC, and stakeholders from around the state, Washington’s Legislature added an additional 7 Basic Law Enforcement Academy courses over three years, with 19 separate classes scheduled between July 2019 and April 2020 (most classes are held in Burien, with two run out of Spokane). Departments across the state still see a need for more classes—as of 2018, the local newspaper in Yakima cited a sixmonth lag in training due to academy class shortages that would leave taxpayers in the city on the hook for $114,000 while new hires were waiting to train—but the increased funding has helped ease the bottleneck.

In Kirkland, Chief Harris has filled all 10 vacancies from 2016. Four new hires for Kirkland’s police department are currently awaiting acceptance into the academy, but the budget boost has been received positively by both law enforcement agencies and city administrators—and it’s helped ease the backlog.

“We’ve been really pleased with the response from Olympia. Kirkland prioritized it, but so did everyone else, so it ended up being a very strong partnership with AWC and with other cities and with lawmakers,” explains City Manager Triplett of the collaborative approach. “I think one of the reasons we’ve had a lot of effectiveness in Olympia is that we don’t just say, ‘Our lobbyist is going to find support.’ We say, ‘A member of the Kirkland City Council is going to go down and actually testify during the hearing.’ And by putting the academy issue on our top-priority legislative agenda, we specifically spoke to legislators who represent Kirkland about why it was important.”

On the heels of the successful legislative push for more academy funding, Kirkland had another win for its local police force—Proposition 1, a local ballot measure passed in the November 2018 election cycle that increased funding for a police task force and resource officers, city mental health programs, and firearms training, gun storage, and homeless shelters through a 0.1 percent sales tax increase. The extra funding doesn’t help with pushing the city’s new recruits through the academy, but the measure does increase job support for Kirkland’s men and women in blue when they do hit the streets.

“It is exciting,” says Harris of Kirkland’s push for better funding of her department locally and through the state. “We’ve done a lot to focus on recruiting and retention of the good officers that we have. The trick is to get them through the academy and to ensure that the state funds classes at a level that is responsive to the needs of police departments. Our city council does a fantastic job staying involved with the state Legislature to support that.”