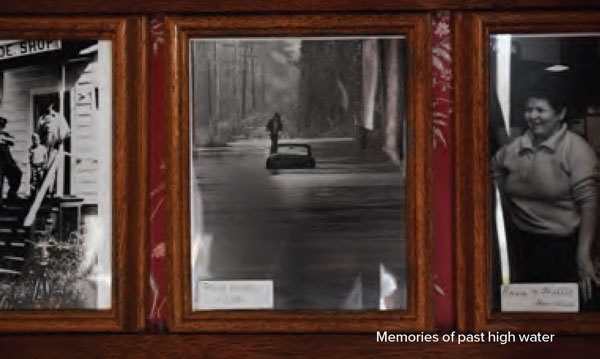

Since the town’s founding along a horseshoe bend in the Skagit River more than 130 years ago, flooding has been a way of life in Hamilton. At Boots Bar and Grill, the local watering hole (motto: “A Flood of Fun!”), double shoulder-high rings around a wooden post near the bar mark where floodwaters crested during the deluge of 2003, and again in 2006. Many Hamilton homes (the 2010 Census counted 113 households and a population of 301) have been raised on cinder blocks. So has Hamilton’s town hall, quartered in an elevated Victorian that doubles as a history museum, where a wall of photos dating back to the late 19th century chronicles the town’s high-water events—including the Flood of 1990, when the late mayor Timothy Bates, a civic icon who held the post for 27 years, stoically drove his hulking Massey Ferguson farm tractor up and down inundated streets, evacuating citizens to higher ground.

Taking a cue from her predecessor, current Mayor Joan Cromley has championed a more audacious, and permanent, evacuation plan: moving Hamilton to a 42-acre former farm, above the floodplain, on the outskirts of town.

“The relocation idea has been in the works for a really long time—since the 1980s,” says Cromley. “It’s something the town’s been working toward, but it took a long time to get an urban growth area designated outside of the floodplain.”

Cromley herself relocated to Hamilton from Pennsylvania in 2002. A year after she arrived, record-breaking late October rains sent the Skagit River cresting at 42.2 feet in Concrete (12 miles upstream), 14 feet above flood stage, the second-highest level ever recorded. Aerial photos of downtown Hamilton submerged under murky river water made national headlines—and caused mass evacuations.

Since then, Cromley, who was elected to Hamilton’s council in 2008 and appointed mayor in 2013, has weathered two more significant deluges—most recently in 2017, when the Skagit breached a makeshift levee along First Street by 18 inches, wreaking havoc. According to a recent report in the Seattle Times, since 1995 the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has received 143 National Flood Insurance Program claims and paid more than $3.3 million in compensation for losses in Hamilton, on top of spending an additional $1.3 million on flood-related grant programs in the town during that time.

So many Hamilton homes have been abandoned, razed, or rendered uninhabitable, the Seattle Times reporter noted, that the town “can feel stretched out, with empty pockets where homes once stood.” Once a house has been flood-damaged beyond half of its market value, FEMA deems it a total loss, prohibiting repair; moreover, state and local laws ban new construction in the floodplain—occupying more than 80 percent of the town’s footprint—which means that Hamilton has slowly and steadily been losing housing inventory (and residents). Most of the homes still standing have been expensively modified—in a town where nearly a third of the population reported poverty-level incomes—yet Hamilton’s supply of housing stock still evokes Florida’s hurricane alley.

“We have a variety of houses that have been raised, usually on concrete foundations with required flow-through openings in the foundations, so they basically have a ground floor that you can’t really use,” says Cromley. “We have people who live right along the edge of the river, and every time it rises, they need to evacuate.”

We have people who live right along the edge of the river, and every time it rises, they need to evacuate.

- Joan Cromley, Hamilton Mayor

Flooding has taken a toll not just on the local economy, but also on the environment. With a $250,000 annual operating budget, Hamilton can’t afford a public sewer system, so each flood breaches septic tanks and dumps waste and trash into the river, critical habitat for Puget Sound’s threatened wild chinook salmon population. After the 2017 flood, the detritus strewn about town once the water receded filled more than 10 dumpsters, even though, by Cromley’s reckoning, “It wasn’t really a big one.”

As recently as 2008, town officials established the Hamilton Public Development Authority and identified a 42-acre parcel outside the floodplain where they hoped to relocate willing residents with state and federal money, but after the land was approved to be added into the town’s Urban Growth Area, the owner decided not to sell. The relocation plan was shelved until 2018, when the landowner approached Cromley about selling. To help finance the purchase, Hamilton partnered with Forterra NW—a Seattle-based nonprofit land trust that specializes in conservation transactions and community development projects—which put down $575,000 for the land (with Hamilton anteing an additional $75,000), located across Highway 20 and outside of Hamilton’s current boundaries. The nonprofit also agreed to help secure financing to pay for the development of the “new” Hamilton from the ground up.

This is where things get interesting. Forterra’s planned development for Hamilton revolves around a completely sustainable, net-zero town center. That means homes constructed with cross-laminated timber (an engineered wood product with a lower carbon footprint than conventional lumber), rooftop solar panels, and a biofiltering wastewater processor to get the new development off of septic. And residents of Hamilton would have the final say on whether they actually ended up relocating to the planned settlement.

“This is not a proposal to move the town—we can’t move anybody,” explains Rebecca Bouchey, Forterra’s director of community development. “Our intention and our goal is to provide a community benefit by building housing outside the floodplain that is available to current residents at a price they can afford.”

Those who would like to relocate can pursue grant-funded buyouts from FEMA for their flood-prone properties, and Forterra plans to work with the community to design new housing that will be affordable for all residents. Still, the plan is in its infancy, and there’s currently no scheduled date to break ground on the project. (Forterra also doesn’t yet have a final cost breakdown of the infrastructure needed for the proposed new town center’s construction, since much of those plans are still in development.)

“There’s some skepticism because the ones who have lived here for a long time have seen this [relocation effort] before,” says Cromley. “It’s a legit concern because they haven’t had any results, but we’re holding the faith on this one.”

Meanwhile, 250 miles southeast in the heart of the Columbia River Basin, the City of Othello has begun to question its reliance on the lower Wanapum Basalt aquifer—a vast underground cache of pure freshwater dating from the last ice age—as its primary source of potable water. In recent years, Othello’s wells, like drinking straws, have been drilled ever deeper into the earth as water levels in the aquifer have diminished, with pumps working harder and harder to keep up with demand.

In June 2015, disaster struck.

“We had triple-digit temperatures for over 30 days in a row, and two of our groundwater pumps went down,” recalls Shawn Logan, a lifelong Othello resident who serves as the city’s mayor and administrator.

Logan prefaces the drama that ensued by explaining that Othello’s population is booming—the town has grown by over a third since 2000, from 5,847 then to 8,132 today. In just the last decade, Logan estimates that 400 more homes have been built, apartment vacancy rates have hovered below 1 percent, and, he says, the hospital’s maternity ward has been busy delivering between 400 and 600 babies a year. (Regional population studies estimate that Othello’s population will more than double in the coming decades, to more than 17,000 by 2035.) Two of the world’s larger potato processing plants are located in Othello, Logan adds, with McCain Foods announcing this year that it plans to expand its local potato processing plant by over 170,000 square feet. This $300 million investment will bring a projected 180 jobs to town and require 11,000 additional acres of regionally sourced potatoes to be farmed—irrigated with aquifer water or surface water from US Bureau of Reclamation canals—to keep the plant running at capacity.

So when the city’s two primary groundwater pumps failed in the middle of an uncommonly hot summer, it was a big deal: Othello consumes nearly four million gallons of water per day, and it had only six million gallons in reserve. Through June and most of July, while a contractor worked feverishly to get the pumps running again, the city rationed water, restricting lawn watering and curtailing what it could send agricultural processors, which consumed 60 percent of the municipal supply. Once the crisis was over, however, city officials knew they needed to address the sustainability of Othello’s water management plan.

“It caused us to realize two things,” says Logan. “We realized that we didn’t have enough storage capacity for the town . . . and that we were 100 percent dependent on groundwater, so we needed to diversify our supply.”

Those two problems were exacerbated by the fact that more and more wells (and new residents taking new jobs at expanding potato processing plants) were simply sucking the aquifer dry—not just in Othello, but all across the region. Groundwater levels in the Columbia Basin have generally been declining for decades, as wells have been drilled deeper and deeper to irrigate farmland and provide potable water to cities and towns. The Western Regional Climate Center describes this area as the “lowest and driest section of Washington,” and despite modest summer rain and 10 to 35 inches of snow each winter, notes that “it is not unusual for four to six weeks to pass without measurable rainfall” during the hot summer months. And those months have been getting hotter and drier. Simply put: there’s not enough supply to meet the Columbia Basin’s demand, and the problem is only expected to get worse.

“There’s not a lot of recharge that happens in these aquifers,” explains Ben Serr, a senior planner with Growth Management Services, who has been conducting outreach to drinking-water providers in the Columbia Basin around groundwater depletion. “The Columbia Basin Ground Water Management Area commissioned studies to carbon-date the water, and on average, the water was 9,000 years old. So basically, if you’ve got an enclosed source of water and a bunch of straws stuck into it, and if you keep drinking from those straws, eventually your water runs out.”

We realized that we were 100 percent dependent on groundwater, so we needed to diversify our supply.”

- Shawn Logan, Othello Mayor

Hoping to preempt that outcome, in May the state Legislature allocated $15 million from its capital budget—the first installment of $40 million in funding that the Columbia River Water Supply Development Program will receive between 2019 and 2021—to build a canal, a booster pump station, and an electrical substation that will divert water from the Columbia to farms in the region as an alternative to tapping wells for irrigation. The plan, being overseen by the Department of Ecology, also includes a pipeline with the capacity to irrigate 16,000 acres of farmland near Moses Lake, 25 miles north of Othello.

Four months earlier, state Representative Mary Dye—a Republican from Pomeroy whose district encompasses Othello—had an audience with high-ranking members of the Trump administration to discuss the completion of a long-shelved Grand Coulee Dam irrigation project. Part of the Columbia Basin Project—which encompasses the dam, Franklin D. Roosevelt Lake, three power plants, four switchyards, and a pump-generating plant—the Grand Coulee currently provides water to irrigate 670,000 acres in east central Washington. While substantial, that coverage falls far short of the 1.1 million acres of farmland the dam was intended to irrigate when the Columbia Basin Project was authorized in 1943. In the 1960s, the state issued temporary well-water rights to farmers in the region, assuming that once the project was completed, farmers would switch to river water for irrigation. But construction stalled, funds were diverted elsewhere, and the full vision of the Columbia Basin Project never materialized, leaving regional farms to rely on well water for irrigation—even to this day.

Completing the Columbia Basin Project, however, has its own unique issues. Environmental groups oppose it, fearing that diverting water from the Columbia for irrigation will further stress the river’s salmon population, which has seen a precipitous decline since the dam was put in place, and will threaten treaty-protected fishing rights of Native American tribes in the area. Despite those concerns, Rep. Dye would like the federal government to earmark $10 million annually over five years to the project, citing the completion of the Columbia Basin Project as a “total game changer for the state.”

Back in Othello, Mayor Logan isn’t waiting to see whether ambitious plans like completion of the Columbia Basin Project will ever materialize. Not long after the city’s water pump failure in 2015, Othello partnered with regional state legislative leaders, the Governor’s Office, and the state departments of Commerce, Health, and Ecology to develop a long-term strategy to secure its water supply to sustain projected growth for the next 75 years. The plans entail a multistage reimagining and overhaul of the city’s water management system that includes drilling a new well to feed a brand-new, 3 million-gallon reservoir. It also includes constructing a state-of-the-art, 12,000-square-foot water treatment pilot test plant that will recycle up to 200,000 gallons per day of wastewater into graywater for irrigation, plus an additional 200,000 gallons per day into potable water that will be injected back into the aquifer via a process known as Aquifer Storage and Recovery (ASR). Cost estimates range from $23 million to $50 million for the wastewater reuse system (depending on what capacity the facility ends up being constructed to handle per day) and an additional $2 million to $3 million for the ASR system.

“This is an expensive problem, and we don’t have it fixed yet—we’re still 100 percent dependent on groundwater,” says Logan. “We needed to have an immediate plan and an intermediate plan, and then we needed a long-term plan. And drilling this next well and doing the water reservoir: that’s the immediate plan.”

Drilling this next well and doing the water reservoir: that’s the immediate plan.

- Shawn Logan, Othello Mayor

Looking to the future, the city has held discussions with McCain Foods about diverting treated effluent from its expanded potato processing facility to the city’s new treatment plant, which would then end up being injected back into the ground to recharge the aquifer.

“There are a lot of pieces; it involves a lot of permitting and a lot of cooperation and coordination,” explains Logan. “But we’re confident in our regulatory team—which includes the Governor’s Office, the Department of Health, the Department of Ecology, and the Office of Columbia River—and we’re all working together toward solutions to become a model for the rest of the state in areas that are experiencing declining groundwater.”

And that’s the thing—Othello thinks its plan will work, but currently there isn’t a comparable system anywhere in eastern Washington to use as a blueprint. Still, the city isn’t going it alone; Othello’s city engineer sits on the steering committee of the Columbia Basin Sustainable Water Coalition, a nascent regional stakeholder group with representatives from Grant, Lincoln, Adams, and Franklin counties and members advocating for agricultural and environmental interests.

“The stakeholder coalition is to keep this issue in the forefront and to continue working on it,” says the Department of Commerce’s Serr, who helped organize the group. “Othello has been great to work with; they are one of the leaders that have really stepped up in the area. . . . I’ve been really impressed by the level of effort they’ve thrown behind this issue.”

If present trends continue, summers will continue to heat up, underground water supplies will continue to dwindle, and the region’s population and industry will continue to grow. So it’s easy to understand when local leaders in Othello say they don’t see any other way but to address their water issues head-on.

Neither do electeds in Hamilton, even if their challenges are distinct. They’re not waiting around for the next flood before they act to find a long-term solution to a perennial problem that has stunted the town’s growth and is only expected to worsen as the climate changes.

“A lot of people will look at this and say, ‘Well, why can’t you raise every single house and continue where you are?’” says Mayor Cromley. “But the limitation of the floodplain has really kept the town from growing the way that every other community in the state of Washington is growing, and Forterra has been working really hard to make sure this is a viable project for the future of our community.”

In Othello, Mayor Logan echoes that forward thinking.

“We want to establish a minimum of a 50-year water supply that takes care of not only what we currently have here, but also the growth that is going to take place in the next 50 years,” he says. “We’re trying to be innovative and creative, and we’re letting industry know: you have a future here in Othello.

And if everything goes according to plan, they may even have some water to spare.