Washington Voting Rights Act implementation

Washington Voting Rights Act implementation

Contact: Shannon McClelland, Sheila Gall

Printable version

Proposals to implement a state Voting Rights Act (VRA) have been introduced and debated in the Legislature for several years, and ESSB 6002 ultimately passed during the 2018 legislative session. Under existing federal law if a Washington voter is a member of a minority group (in race, color, or language) and believes that local voting procedures denied them equal opportunity to participate in the nomination and election process to elect a representative of their choice, they can challenge the local procedures in federal court.

Any local voter can challenge a city’s voting system in state court after providing the city with notice.

Under the new state VRA, any local voter can challenge a local governments’ voting procedures in state court after providing the local jurisdiction with notice. The VRA also amends state statute to expressly allow non-charter code cities, second class cities, and towns to voluntarily adopt district-based election systems (or other types of voting methods) in general elections to address a potential violation of the act.

Main provisions of ESSB 6002

Voluntary change

- Cities can proactively change their election system to remedy a potential violation.

- Changes can include, but are not limited to, a district-based system for the general election.

- Public notice is required prior to adoption of a remedy.

- If a significant segment of city residents speaks a language other than English and have limited English proficiency, the city must provide the following public notice in the language that diverse residents of the city can understand, based on demographic data:

- Written and verbal notice; and

- Airing of radio or TV public service announcements.

- Significant segment is defined as 5 percent or 500 residents – whichever is smaller.

- Districts must conform to requirements outlined in the VRA.

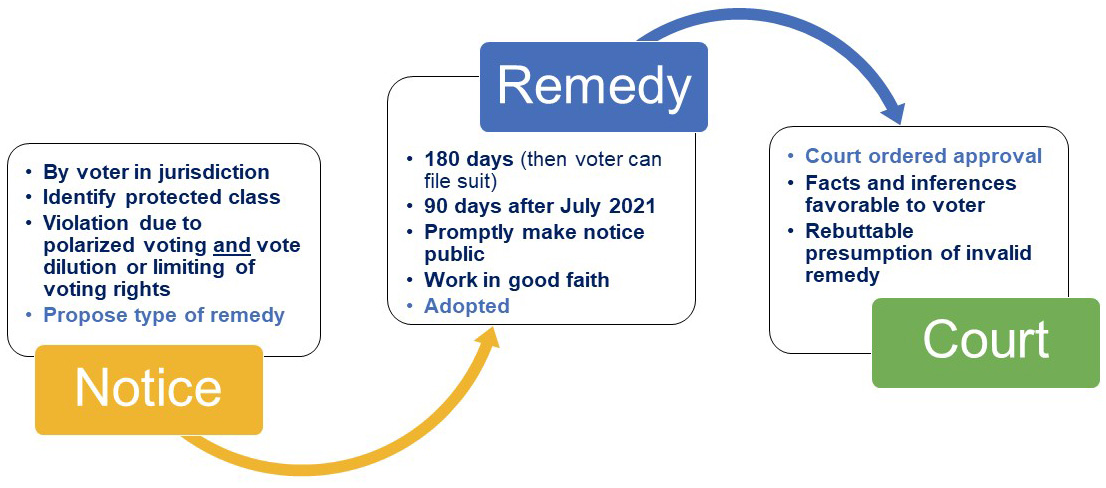

Notice

- A local voter must provide notice to a local government if they intend to challenge the election process.

- The jurisdiction must work in good faith with the voter to determine if there is a plausible violation and, if so, to propose a remedy.

- The city has a statutorily specified time to adopt a remedy and have it approved by a court (see Implementation timelines below).

- The city must consider electoral data, demographic data, and any other relevant data in crafting a remedy.

- During review of the jurisdiction’s adopted, proposed remedy, the court views the facts and inferences in favor of the voter; the proposed remedy is presumed invalid.

- If another notice is received during the notice period, the city must work in good faith with that voter as well, but the law does not provide additional time to the notice period.

Lawsuit

- If the jurisdiction does not receive court approval of its adopted remedy by the notice period deadline, the voter may file a claim in state court.

- If a violation under the act is determined, the court may order:

- the jurisdiction to adopt a district-based election process;

- redistricting; or

- another remedy.

- The court must order new elections. The timing of the order will determine at which general election the changes take effect.

- Cities are required to publish the outcome, summary, and legal costs of court action on the city's website.

Safe harbor

- If the local jurisdiction adopts a court-approved remedy, no legal action may be brought against the local jurisdiction for four years.

- Exception: If the city makes a change to its election system that impacts the approved remedy.

- No action may be brought against a jurisdiction that made a change under the federal VRA in the previous decade until after a redistricting change is made due to the 2020 Census.

Key definitions

Polarized voting: “Voting in which there is a difference [as defined in federal VRA caselaw] in the choice of candidates or other electoral choices that are preferred by voters in a protected class, and in the choice of candidates and electoral choices that are preferred by voters in the rest of the electorate.”

This is really a definition of racially polarized voting, and that is what the law is designed to address. It may help to think of it that way when you see the term polarized voting in this law.

Protected class: “A class of voters who are members of a race, color, or language minority group [as defined in the federal VRA].”

The federal VRA defines “language minority group” as American Indian, Asian American, Alaskan Natives or of Spanish heritage.

Implementation timelines

- The law took effect June 7, 2018.

- As of July 19, 2018, a voter may submit a notice to a local government if they intend to challenge the election system.

- Notice period deadline before a suit may be filed in state court – 180 days if notice is received by July 1, 2021, and 90 days if notice is received after July 1, 2021.

Questions

How do we know if our election system violates the VRA?

The law states: “No method of electing the governing body of a political subdivision may be imposed or applied in a manner that impairs the ability of members of a protected class to have an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice as a result of the dilution or abridgement of the rights of voters who are members of a protected class.”

The problem the law is trying to address:

The structure or practices of an election system that dilutes the votes or limits the rights of a protected class, resulting in an unequal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice.

To determine whether the structure of your city’s election system violates the law, you will need to evaluate your demographic and electoral data. Risk factors to look for include the size and concentration of protected-class voters, complaints about the existing election system, or history of candidates supported by protected-class voters who have been unsuccessful. A successful candidate who was supported by protected-class voters does not automatically mean that your election system does not violate the VRA.

Which cities does this impact?

All cities can take voluntary action under the law. The notice-to-sue provision applies to cities and towns with a population of 1,000 or more. It also applies to school districts with 250 or more full-time students, counties, fire districts, port districts, and public utility districts. It does not apply to statewide elections.

If we are making changes under the voluntary provision of the law, is the public notice requirement for non-English speaking residents only for the members of the “language minority group,” as defined in federal law?

No, it is broader. If your city has a significant segment of residents that have limited English proficiency, the city must provide public notice in “languages that diverse residents of the city can understand, as indicated by demographic data.”

What does it mean that the city’s remedy is presumed invalid? (i.e. rebuttable presumption that the court will decline to approve the city’s remedy)

During review of the proposed remedy, the court would traditionally give deference to the city’s adopted remedy because it was the result of council legislative action. In short, the city’s remedy would be presumed valid and the voter would have to argue against that presumption (i.e. why the city’s proposed remedy is not valid).

However, the VRA changes the legal standard to one that favors the voter. Under the VRA, the city’s proposed remedy is presumed invalid – and the city has to argue that it is valid. In sum, the burden is on the city to prove their adopted remedy will address the alleged violation.

What does it mean that the court views the facts and inferences from the perspective of the voter challenging the city’s election process during the notice phase?

Traditionally, the court hears each party’s view of the facts and determines – based on the evidence – which view of each fact is more credible. The court then makes factual findings in its order, in addition to conclusions of law based on those factual findings.

The VRA however, determines factual findings in favor of the voter. Under the VRA, the court will view all the facts – and inferences from those facts – as true from the voter’s perspective. The court will then review the proposed remedy in light of those facts to determine if, as a matter of law, the proposed remedy will address the alleged violation – similar to the standard of review used by courts for motions for summary judgment.

If we change to districts, how does this affect the current council seats?

Depending on the timing of adoption of districts or other changes, special elections would be required. If districts are adopted voluntarily or court-ordered during the two months between the first Tuesday after the first Monday of November and on or before January 15 of the following year, the city is required to hold special elections at the next general election. If adoption occurs in the nine months between January 16 and on or before the first Monday in November, changes to the city’s election system would not occur until the following year’s general election.

What if only five percent of our population meets the definition of a protected class?

It is unlikely that a voter would be able to show vote dilution in this case. However, if the entire protected class population lived in one district, the likelihood of showing vote dilution increases. Unlike its federal counterpart, the VRA does not require that members of a protected class live in a compact area in order to prove a violation – they could be scattered across the city.

Where can I find more information on the Voting Rights Act?

Data sources

Demographic data: AWC Data Portal – Your City Snapshot, Measuring Diversity

Electoral data: Secretary of State City Registration Demographics

Electoral data: Secretary of State Election results

Governance data: MRSC Creating Inclusive Communities

Disclaimer: The content of this website does not constitute legal advice and is not intended as a substitute for seeking the counsel of your city attorney.